Farmers are used to counting their harvest in tons, but today there’s another metric – tons of CO₂ that can not only be stored in the soil but also sold.

For Ukrainian farmers, carbon credits are another opportunity to generate income from what they do daily: working the land, growing crops, and preserving soil fertility.

The concept is simple – demonstrate that the farm is actually retaining carbon in the soil. And do it in a way that can be verified according to international standards.

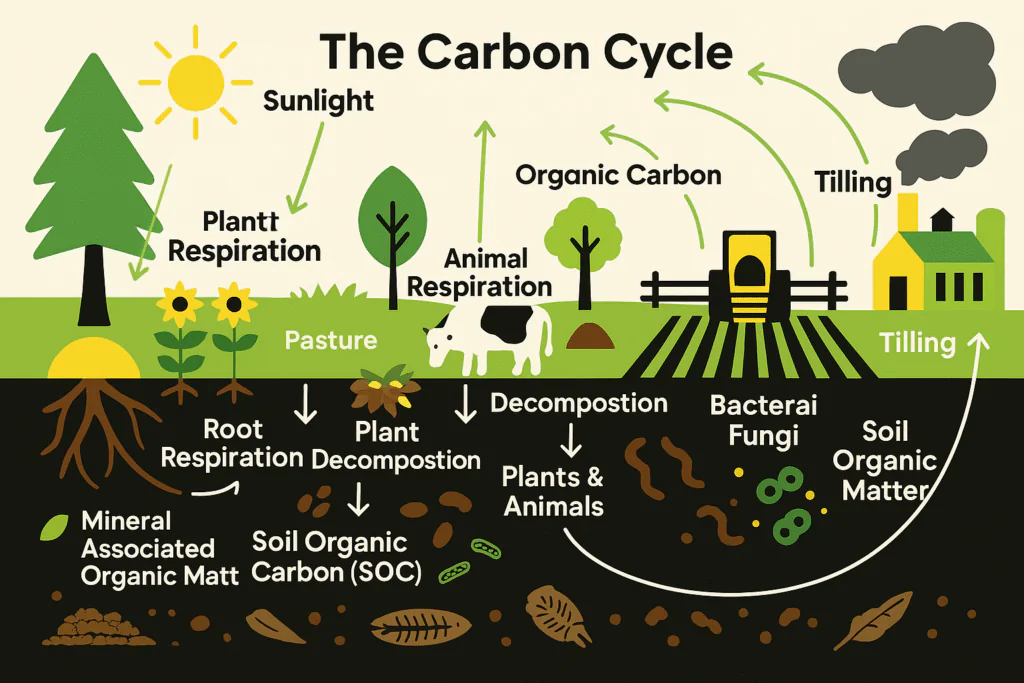

But before starting, it’s important to understand how soil accumulates carbon and why some technologies promote this while others lead to losses.

How to add carbon to the soil

The simplest way is to leave more organic residues in the field. Every stem, every root that decomposes naturally gradually enriches the soil with organic carbon.

Cover crops are another effective tool. They retain carbon between main seasons, protect the soil from overheating and erosion, and after mowing, turn into natural fertilizer.

Another important element of carbon farming is the use of organic fertilizers. Manure, compost, or residues from previous crops return carbon to the soil that once left it with the harvest. Unlike mineral fertilizers, organic matter nourishes not only plants but also microorganisms that form the soil structure and help retain carbon in a stable form.

A well-planned crop rotation also works well. When crops with deep root systems are followed by plants that leave large biomass, the carbon balance in the soil steadily increases.

How not to lose accumulated carbon

Even if soil has been accumulating carbon for years, it can lose it in one season. Let’s understand why this happens.

During photosynthesis, plants absorb carbon dioxide from the air and convert it into organic carbon. Part of this carbon remains in the form of root residues and gradually transitions into the soil. This is how organic matter forms, on which fertility depends.

Deep plowing disrupts this system. When the layer is turned over, carbon from the lower layers reaches the surface, where it combines with oxygen and turns back into CO₂. What could have remained in the soil for years simply evaporates into the atmosphere.

The life cycle of organic carbon in the soil

This is why modern technologies that reduce tillage intensity or completely abandon plowing (No-till) allow more carbon to be retained in the soil and improve its structure.

The mechanism is simple: fewer losses – more carbon in the soil. Now let’s see how to implement this in practice.

Where should a farmer start

Next, everything is determined by preparation: what data to collect, what changes to record, and how to show the result. But it’s worth starting not with papers, but with the field.

Step 1. Understand which technologies you are already using and what can be changed to make the soil retain more carbon.

If your farm still uses a traditional tillage scheme with plowing, a large number of machinery passes and fertilizers, this is where you can start making changes. It’s a good starting point because deep plowing leads to the loss of most carbon.

Next, it’s worth determining which new practices can be added to make the soil start accumulating more carbon. These could be cover crops, well-planned crop rotation, leaving organic residues, or gradually transitioning to minimum tillage.

It’s precisely the contrast between old and new approaches that captures the effect, which then becomes the basis for carbon credits.

Sometimes small changes are enough: reducing the number of machinery passes, not touching stubble after harvesting, or leaving some residues on the surface to see the first results in a year or two.

Step 2. Choose fields to participate in the project

It’s best to start with a few fields where it’s easier to control changes and record data. These can be areas that are most convenient to convert to minimum tillage or sowing cover crops. The portfolio of fields can be expanded annually.

This approach allows you to check how technologies work in your specific conditions while not creating an extra burden on the production process.

It’s important to remember that not every field can be included in a carbon project.

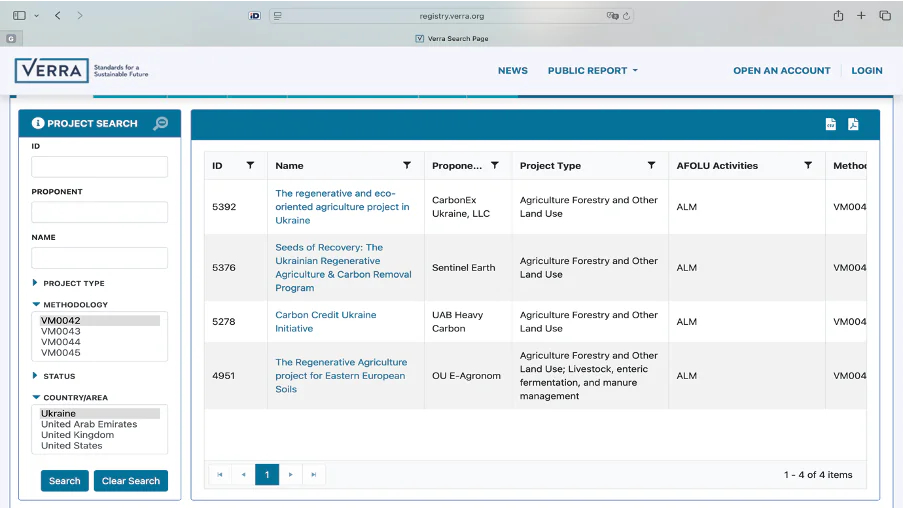

According to international standards (particularly Verra VCS, methodology VM0042 – Improved Agricultural Land Management), plots must meet several basic criteria:

- Permanent land use. The type of land has not changed for at least the last ten years – the field has not been converted from pastures or forests to arable land.

- Confirmed right of use. There must be documents for each plot: an extract of ownership or a lease agreement.

- Known cultivation history. Basic data is needed for at least the previous three years, but necessarily for a full crop rotation cycle.

- No clearing of natural areas. The project cannot cover areas where natural ecosystems have been destroyed in the last ten years.

- Possibility of measurements. Access must be provided in the field for soil sampling to confirm the amount of accumulated carbon.

- No double counting. The same plot cannot participate in several carbon or environmental projects simultaneously.

Step 3. Prepare baseline data about the fields

It’s necessary to collect all information that will show exactly how the farm worked before.

This data will become the “starting point” for comparison, as carbon credits are awarded not just for new practices, but for a change in the method of cultivation.

In most cases, you need to prepare a brief description of each field:

- which crops were grown in recent years;

- what type of tillage was used (plowing, disking, minimum tillage, No-till);

- number of machinery passes and approximate fuel consumption;

- fertilizer application rates (mineral and organic);

- leaving or removing plant residues;

- presence of irrigation, grazing, or other specific factors.

It’s also important to indicate whether new practices are planned, such as cover crops, rotation with legumes, or reduced tillage.

These changes will be taken into account during modeling and verification of emission reduction potential.

Field contour

Separately, you need to determine the exact boundaries of each plot.

The contour is a digital file or coordinates by which the field can be seen on a map. It’s needed for satellite monitoring, verification of land use history, and future measurements.

Usually, it’s sufficient to provide the contour in KML, SHP, or GeoJSON format, which can be easily exported from any agro-platform or even from Google Earth by marking boundary points on the map.

Step 4. Choose a carbon project developer

Even if the farm is ready for changes, going through the entire process from data collection to selling carbon credits without appropriate technical expertise is quite difficult.

Therefore, it’s most convenient to turn to a company that already has experience in developing such projects and can take on the technical part of each stage: from preparing documentation to verifying results.

The developer company (or project organizer) takes on the full cycle of work:

- registers the project with an international standard, such as Verra VCS;

- prepares technical documentation and conducts emission modeling;

- organizes soil sampling and laboratory analyses;

- accompanies the audit and confirms the results of emission reduction or absorption;

- submits results to the registry, after which carbon credits are issued by the standard and can be put up for sale.

This way, the farmer can focus on their work in the field, while all the technical and bureaucratic parts are handled by specialists.

It’s only important to ensure that the company has experience in developing projects specifically in the agricultural sector, works with recognized standards, and provides transparent cooperation conditions.

Carbon project developers can be found in the open registry of the Verra standard (https://registry.verra.org/app/search/VCS/All%20Projects).

All basic information is available there: project descriptions, documentation, as well as contacts of companies and responsible persons.

This is a convenient way to check the experience of a potential partner and ensure that they work according to international rules.

It’s precisely the contrast between old and new practices that captures the effect of reducing emissions and accumulating carbon in the soil.

What income can a farmer get from carbon credits

Depending on the scale of the farm, soil type, and implemented practices, a farmer can receive additional income of up to 60 dollars per hectare per year.

However, the amount of payments depends on the amount of carbon that the soil actually retains, as well as on the model of participation in the project.

What’s Next?

In the next column, we’ll examine how the price of a carbon credit is formed, what the farm’s income depends on, and what distinguishes a quality project from an average one.